421 Hazel Brake

Lots 33 and 34

“The Westenberg House”

Built in 1905

Currently owned by Peter Parry

Charles (1860-1927) and Jesse Westenberg (Dewolfe)(1856-1948) built their cabin in 1905. They had two daughters, Helen (1886-?) and Bethany (1898-1983) and lived in Berkeley at 2811 Benvenue Avenue. That house is now a Berkeley Historic Landmark.

Charles was a venture capitalist who owned a 26,000 acre rubber plantation in Mexico and a gold dredging company in addition to many other companies. Jesse was a missionary whose life was spent uplifting the downtrodden and poor.

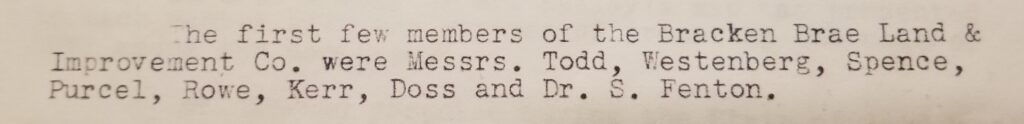

The Westenbergs were among the founders of Bracken Brae. Charles served as a trustee and many real estate transactions went through him. Although they were among the wealthiest families in Berkeley and owned a magnificent 5300 square foot mansion, they chose to spend months at a time at their cabin in Bracken Brae. The cabin stayed in the Westenberg family for 38 years.

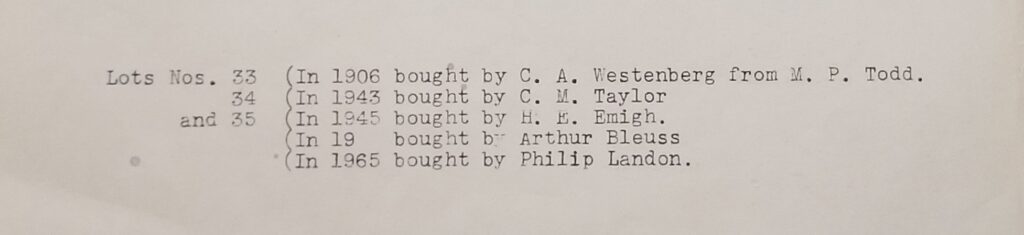

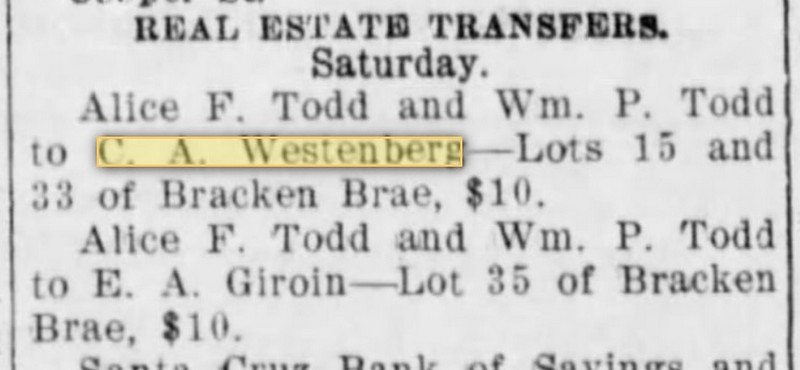

In 1905 Charles and Jesse Westenberg purchase lot 33 and build their cabin on it.

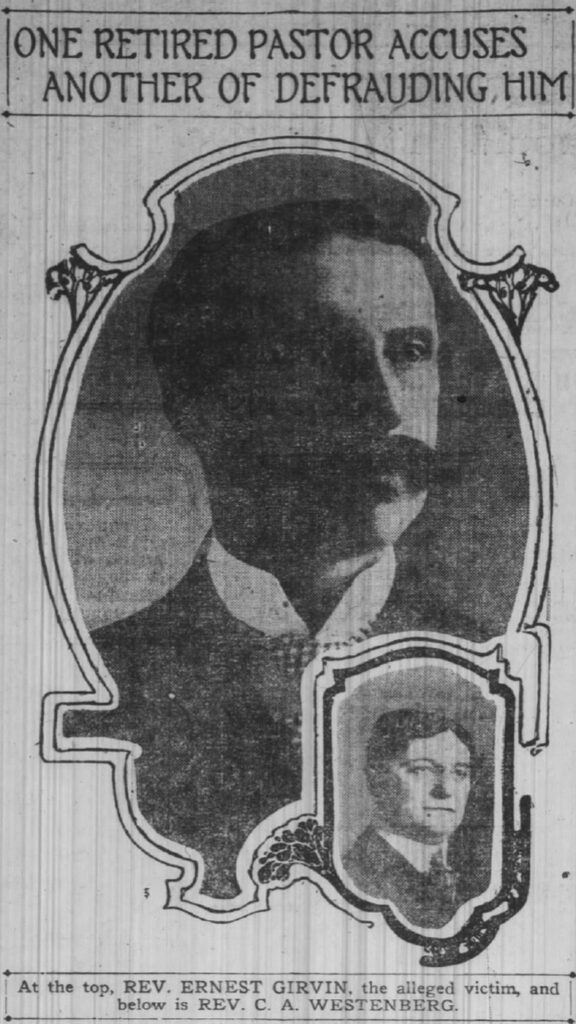

Charles Westenberg purchase lot 15 and lot 33 (upon which he builds his cabin). The date list in the History of Bracken Brae is incorrect and may reflect the fact that all Bracken Brae records were destroyed in the 1906 earthquake. E. A. Girvin (misspelled) was a fellow reverend who is mentioned in articles below.

The first directors of Bracken Brae are C. A. Johnson (I think this is an error and should be C. A. Westenberg of 421 Hazel Brake), Edgar Bishop (owner of the lot at 511 Hazel Brake), Archie Kerr (of 530 Hazel Brake), Clinton McAllister (of 435 Hazel Brake), and Purcell Rowe (of 445 Hazel Brake)

The Westenberg Family

Charles marries his wife, miss Jessie Fremont de Wolf. The Westenberg’s were wealthy venture capitalists. They owned a 26,000 acre rubber plantation in Mexico in addition to gold mining interests and were responsible for launching many other companies.

Jesse Westenberg has worked tirelessly since the devastation of the 1906 earthquake 3 months earlier and desired a much needed rest at 421 Hazel Brake in Bracken Brae.

The Westenbergs were homeless advocates as were many founders of Bracken Brae.

The following article is from the Berkeley Heritage web site by Daniella Thompson : berkeleyheritage.com/berkeley_landmarks/westenberg.html

Old Berkeley may have been solidly Republican, but it never lacked for colorful and even eccentric characters. How else to explain the flights of fancy some early Berkeleyans commissioned when building their homes a century ago?

One wouldn’t expect a Methodist minister to build an oversized storybook house, yet this is precisely what went up at 2811 Benvenue Avenue in 1903. The owner, Charles Albert Westenberg (1862–1927), was a self-contradictory man, adamantly opposed to card playing and dancing yet not at all scrupulous about profiting from the despoliation of nature or the ruination of his friends.

Westenberg was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the son of a German agar maker. His brave mother gave birth to 14 children and outlived at least three of them, as well as her husband.

While Charles was still a child, the family moved to Ohio, where he grew up and met his first wife, Louise Arndt, the daughter of Methodist physicians. Charles and Louise’s only child, Helen Lois, was born there in 1886.

Having been ordained as a Methodist Episcopal minister, Westenberg set out for southern California. In 1891 he was posted to San Diego County, serving at the First United Methodist Church in National City and at St. Paul’s Church of the Voyager in Coronado. Louise died that year, leaving him with the 5-year-old Helen.

From 1892 to ’95, Westenberg was pastor of St. Paul’s Church in San Bernardino. During that period, his brother, Robert Campbell Westenberg, appeared in southern California and took charge of Methodist churches in La Mesa (1895), Prospect Park, Los Angeles (1896), and Santa Monica (1897) before returnig east.Charles met his second wife at the Friday Morning Club of his San Bernardino church. Miss Jessie DeWolfe (1856–1948) was a Vermont-born schoolteacher of Dutch ancestry and a devoted Methodist. At the time, Miss DeWolfe was in charge of teaching the girls at the California State Reform School in Whittier.

The couple was married in Los Angeles on 14 January1895 before moving to Santa Barbara, where Charles took over the pulpit at the First United Methodist Church and the chaplaincy of the Masonic Lodge. One of his accomplishments in Santa Barbara was the establishment of a “Fishermen’s Club,” a band of young men whose task it was to secure a list of all the tourists at the local hotels and boarding houses and to invite them to attend the church during their stay. In 1899, the Record of Christian Work commended Westenberg on this work, which helped counteract the evil of Sunday sightseeing.

Mrs. Westenberg wasn’t idle either. In 1897, she was secretary of the Woman’s Home Missionary Society of the California Conference of the ME Church (she would be elected president seven years later). On 11 April 1898, she gave birth to Margaret Bethany Westenberg and now had two girls to rear.

Charles Westenberg’s tour of duty in Santa Barbara came to an end in 1899. The family moved to San Francisco, where Charles became superintendent of the Boys’ and Girls’ Aid Society. In June 1900, he took his 60 wards on a six-week camping vacation in Cazadero. He still preached occasionally, but—as Jessie would tell Hal Johnson of the Berkeley Gazette four decades later—his voice gave out in 1901, forcing him to give up the ministry and go into business as a broker.

The impetus appears to have been a trip he made in 1900 to Palenque, Mexico, as a member of a committee sent to investigate the property of the Chiapas Rubber Plantation and Investment Company. The other committee members were Los Angeles Superior Court judge Lucien Shaw (later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of California), Santa Barbara postmaster Orlando W. Maulsby, Reverend L.M. Hartley of Redlands, and Ernest Alexander Girvin, a California Supreme Court reporter and Berkeley resident.

Girvin, a close friend and future business ally of Westenberg’s, had attended Hastings College of the Law in 1881. He professed sanctification that year, joined the Trinity Methodist Church in San Francisco, and received a local preacher’s license. At the age of 27, he co-authored the book Pure English: A Treatise on Words and Phrases, or Practical Lessons in the Use of the Language (A.L. Bancroft & Co., 1884). In 1896, dissatisfied with the rigidity of the Methodist Church, he made the acquaintance of Dr. Phineas F. Bresee, who had just founded the evanglical Church of the Nazarene in Los Angeles. Early the following year, Girvin organized the First Church of the Nazarene in Berkeley and became its first pastor, fulfilling this role alongside his court work.

Returning from Mexico, the committee released a flattering report on the Chiapas plantation, as the San Francisco Call reported on 16 December 1900: “24,000 acres of the choicest rubber land of Mexico, upon which over 700,000 vigorous young rubber trees now thrive. On the plantation also are numerous mahogany trees, some of which are of prodigious growth, thus demonstrating the richness of the soil.”

The enterprise clearly made an impression on Westenberg and Girvin, since they both got involved in the rubber business. The former was president of the Rio Michol Rubber Plantation Co. (with Girvin as corporate secretary), managing director of the Chiapas Rubber Plantation Co., and a broker for their securities. At the same time, he acted as president of the United States Gold Dredging Co., again with Girvin as secretary.

The Westenbergs lived in San Francisco until 1903. Fortune must have smiled on Westenberg’s business dealings, for in February 1903—a little over two years after leaving the ministry—he bought three adjacent lots on Benvenue Avenue, in the recently subdivided Berry-Bangs Tract.

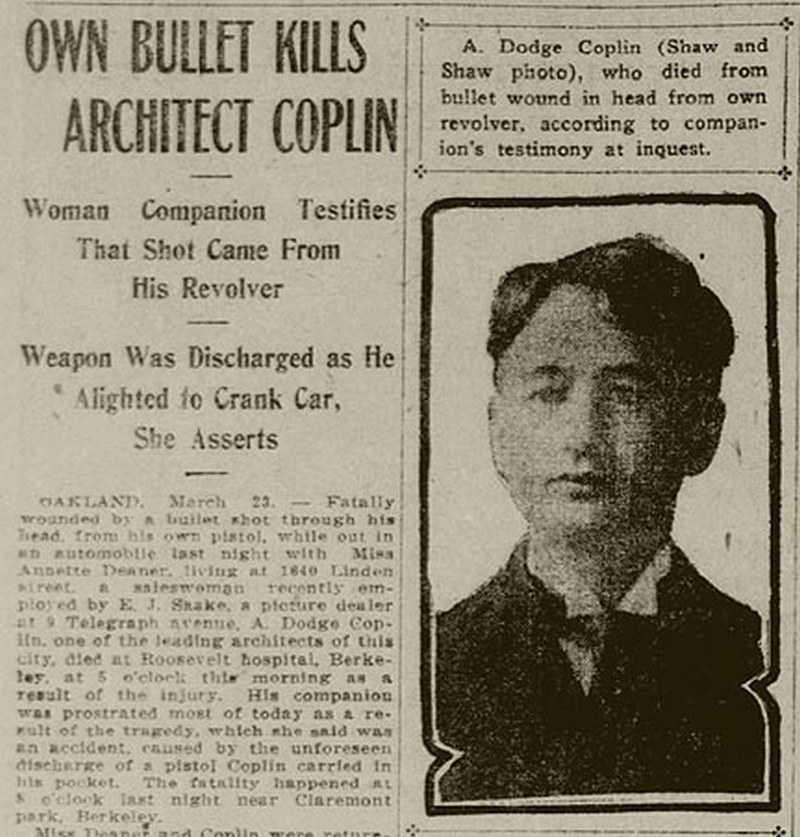

His new home, designed by Albert Dodge Coplin (1869–1908), cost a substantial $11,000. Coplin, one of the more popular and prolific architects in the East Bay, was the son of Alanson Coplin (1835–1906) a clergyman who had withdrawn from the Methodist Church to form his own evangelical Church of Christ. The Coplins settled in Oakland in the late 1870s, and Coplin père put food on the table by acting as general agent for Dr. Warner’s Health Corsets and other “dress reform and hygienic garments.” Alanson’s Corset House was a longtime fixture at 1157 Broadway, where young Albert worked as a clerk before turning to contracting and building in the early 1890s.

As in the alliance with Girvin, it may have been the Methodist connection that drew Westenberg and Coplin together. In designing the Westenberg house, Coplin pulled out all the stops. The house was the first on its block, surrounded by open land that had been wheat fields as late as 1902. Coplin heaped on steep gables that echoed the Berkeley hills looming to the east.

Clad in clapboard on the ground floor and shingles above, the house is fronted by one of Coplin’s signature asymmetrical clinker-brick chimneys (a similar chimney may be seen on the Roy Block House at 2920 Hillegass Avenue). Situated on the northernmost parcel of a triple lot, the house presented its flank to the street, facing a vast garden to the south. The massive front door, almost as wide as it is tall, is set in the south façade between enormous twin gables. In the rear, the old converted barn and carriage house are still extant.

The house received a detailed description in the Oakland Enquirer of 29 September 1903:

ANOTHER BEAUTIFUL RESIDENCE IS ADDED TO THOSE OF CLASSIC BERKELEY’S SLOPES

UNIQUELY ARRANGED HOME OF C. A. WESTENBERG AT BERKELEY, DESIGNED BY A. D. COPLIN.

Nearing completion on the slope south of the university and among Berkeley’s best residences is an attractive dwelling out of the usual stereotyped order, which has been designed by Architect A. D. Coplin for C. A. Westenberg, who is identified with large Mexican plantation interests. His beautiful new home is located on the east side of Benvenue avenue, near Stuart street, Berkeley. The grounds will be laid out in landscape style with a choice apportionement of fruit trees, palms and other growth that typify many beautiful home spots of the south.

The garden was Jessie Westenberg’s pride and joy. When Berkeley Gazette columnist Hall Johnson visited her in 1943, he wrote that “the gardens look as if they had been lifted from Golden Gate Park and brought across San Francisco Bay.” Those being war years, the Westenbergs cultivated a large Victory garden behind the ornamental shrubs and roses.

After the house was completed in October 1903, Coplin was a favorite dinner guest. He never forgot to bring chocolates for little Bethany, while his own two children—the products of a failed six-year marriage—were all but ignored. In 1908, when he was killed in a freak accident involving his own pistol while on a car outing with a young woman, the former Mrs. Coplin, a music teacher who divorced him on charges of cruelty, said only, “I am too busy teaching to talk about Mr. Coplin.”

In the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, Charles Westenberg moved his office from the Crocker Building in San Francisco to the First National Bank Building in downtown Berkeley. Here he engaged in a succession of business enterprises, some more profitable than others.

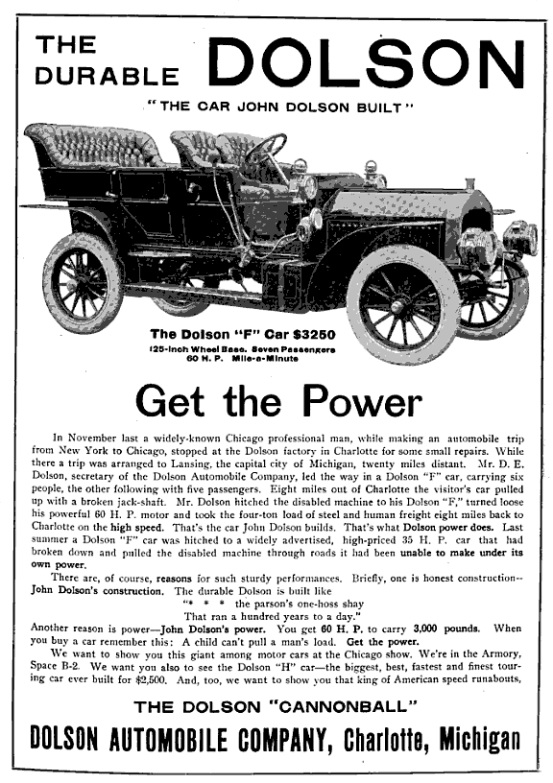

For a while he was treasurer (Girvin was secretary) of the Copper Canyon Mining Co. of Mayer, Arizona, organized in 1905 and apparently moribund by 1909. In May 1907, Westenberg was one of a group of Berkeley capitalists who formed the San Francisco Motor Car Company. In their planned West Berkeley factory, they intended to build “high-grade delivery wagons and motor vehicles of all types used in freight transportation,” reported the Oakland Tribune. The factory was never built, but the company acted as agent and dealer of Dolson Automobile Co. of Charlotte, Michigan, selling the now forgotten Dolson car.

Charles Westenberg and E. A. Girvin (both Bracken Brae property owners) start an automobile company, the largest in the west.

The United States Gold Dredging Co. and the Consolidated Gold Dredging Co. also did not fare well. On 8 Jan. 1911, Ernest Girvin filed a lawsuit against his old friend, accusing him of having defrauded him and other inverstors of $150,000 by misrepresenting the value of the mining claims. “Westenberg is the only one who has made anything of this company,” complained Girvin in court. Later the same month, another disgruntled investor launched a separate suit.

Only a year before being sued for fraud, Westenberg addressed the congregation of the College Avenue Methodist Church, denouncing the sins of card playing and dancing. He wasn’t alone in this battle for redemption. Another clergyman brother of his, J.C. Westenberg, was waging war on sin in San Francisco’s Barbary Coast

The newspapers did not report the outcome of the lawsuits, but Westenberg was soon enough out of the gold dredging business and into the sheet metal business. The Mexican rubber plantations petered out during the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s, “when the laborers became more interested in fighting each other than working on the plantation,” as Jessie Westenberg told Hal Johnson. Now Charles turned his attention to real estate, and in the last decade of his life was listed as a building contractor.

Jessie survived Charles by 21 years and continued active in the community. From 1926 to 1928, she headed the fundraising effort for rebuilding the Beulah Rest Home for aged Christian workers at 4690 Tompkins Avenue in Oakland. She was a charter member of the Twentieth Century Club and prided herself on having been the second customer at J.F. Hink and Son’s store the first day it opened in Berkeley on the southeast corner of Shattuck Ave. and Kittredge Street.

Jessie and Bethany remodeled some of the interiors after Charles’s, death, “modernizing” the living room, dining room and kitchen. The fireplaces in the two former rooms fell victim to the renovations.

Bethany Westenberg, an alumna of the University of California, taught in a San Francisco private school before becoming an advisor of the Alpha Chi Omega. She lived in the house until the mid-1970s, continuing to tend to her large garden. During the residence of the next owner, the garden was reduced by half, as a charming cottage was moved in from the 2900 block of Benvenue Ave., where it impeded the expansion of the Berkeley Public Library’s Claremont branch. Fortunately, the newly enacted Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance stood in the way of its demolition.

The Westenberg House was designated a City of Berkeley Landmark on 7 September 2006.

The Chiapas Rubber Company has been very profitable for the Westenberg family.

Rev. Westenberg declares that one of the biggest sins in Berkeley is playing cards.

Charles Westenberg is in a legal battle over a gold mine with E. A. Girvin, who is also a Bracken Brae property owner.

The Westenberg’s are some of the prime movers in the conversion of the Bracken Brae Land and Improvement Company to the Bracken Brae Country Club in 1926.

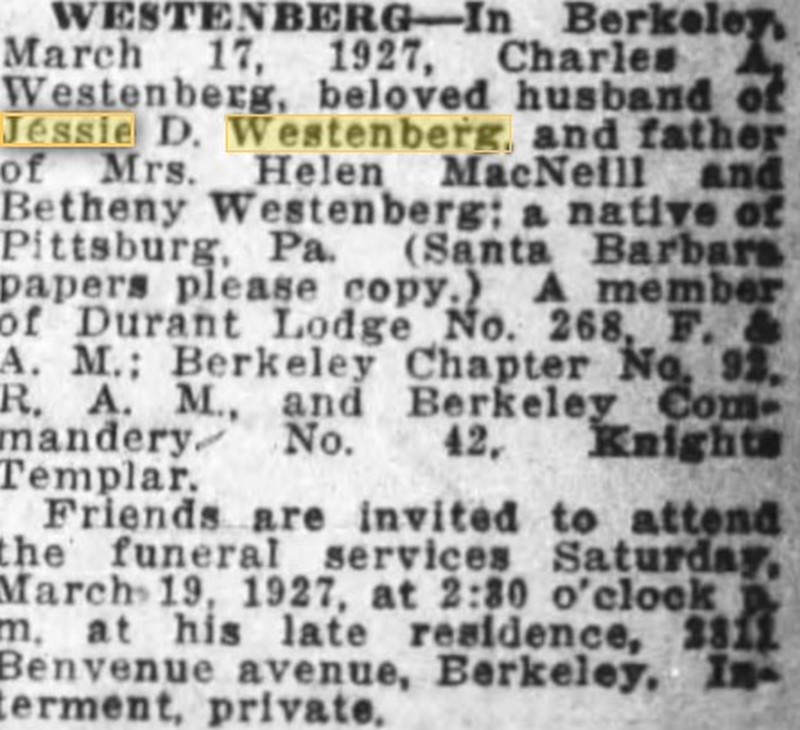

Charles Westenberg dies March 17th, 1927

Bethany Westenberg, Charles and Jesse’s daughter, is hosting a party at Bracken Brae.

The cabin has put in Bethany’s name and is sold to Carl M. Taylor. The cabin had been in the Westenberg family for 38 years.

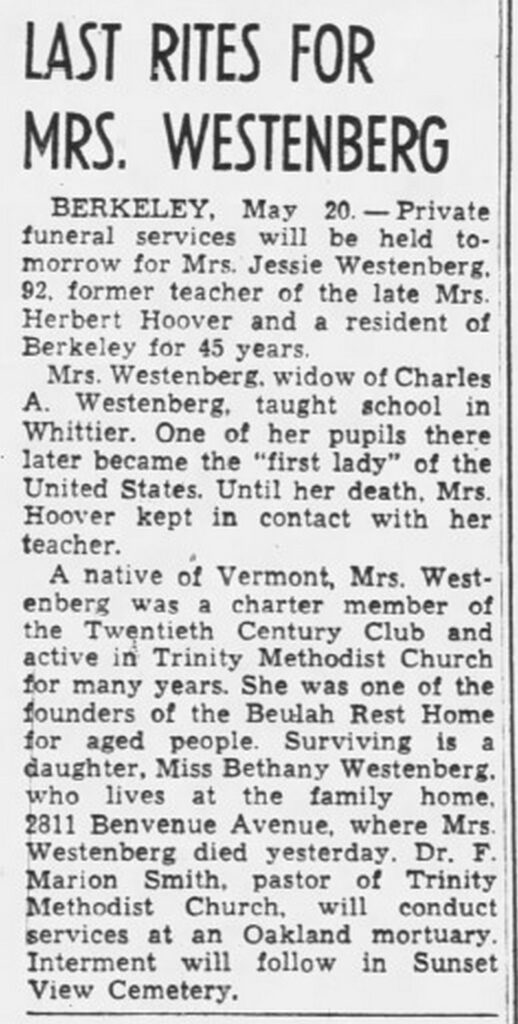

Jesse Westenberg obituary. She dies 5 years after the cabin is sold.

In 1945 the house is purchased by H. E. Emigh, a Chevrolet dealer in Santa Cruz.

At an unknown time between 1945 and 1965 the House was purchased by Arthur Bleuss, a butcher from San Mateo. This person would have known my grandfather, who had a butcher shop in San Carlos at the time.

The house was purchased in 1965 by a man named Philip Landon, whose name did not come up with any results. By this time people had more privacy and names became more and more common. The house was bought by the Parry family in 1973 (?)